A WWII-era poster warning citizens not to discuss ship, troop, or supply movements. Its text is strangely apropos in distinguishing between real political speech and careless chatter. (Photo credit: NARA – 535383)

What follows is an abridged compilation of my recent series, “Money in Politics.” The essay is forthcoming in a Swarthmore College student publication entitled Left of Liberal.

Equivocating “Speech”: Political Advertising, Mass Media, and Human Excellence

Since the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. FEC, the United States government has treated anonymous monetary contributions to political organizations as constitutionally protected free speech. Much has been made of the practical implications of Citizens United, especially regarding its alleged support of plutocracy. While I am generally sympathetic to such criticisms, I aim to evaluate a different premise of the Citizens United ruling: that independent expenditures are a form of constitutionally protected speech; simplistically, that money equals speech.

In fairness, the Court does not adhere to this premise directly. It cites the majority opinion from another case, Buckley v. Valeo: “A restriction on the amount of money a person or group can spend on political communication during a campaign necessarily reduces the quantity of expression by restricting the number of issues discussed, the depth of their exploration, and the size of the audience reached…. The electorate’s increasing dependence on television, radio, and other mass media for news and information has made these expensive modes of communication indispensable instruments of effective political speech.” In other words, money is not speech per se, but because we live in a society that has commoditized major segments of public fora, we should protect persons’ ability to purchase space in such fora.

Its naturalism fallacy notwithstanding, the Court ignores substantial reasons to distinguish between monetary expenditures (a market transaction) and political speech (a political interaction). The very interests that the Court cites in establishing the historically contingent relation of money to speech – i.e., it’s ability to create broad, deep, and inclusive discussion of issues of public importance – are precisely those interests that no market transaction can achieve. Forcing speakers to buy entrance into public forums fundamentally subverts the political process.

—–

Monetary outlays do not have any speech content unless accompanied by some other communication. A Super PAC can spend a small fortune espousing the benefits of a healthy breakfast or just air hours of white space, if it so desires. Buying up ad space (the monetary expenditure part) is distinct from imbedding content within those advertisements (the political speech part). Even boycotts and other forms of “economic speech” only gain their political content from the message accompanying the decision to purchase or not to purchase a certain product. Otherwise, that decision is relegated to the entirely private, economic realm of personal preference, where it lacks the essential publicity of political action.

The Court thus relies solely on the belief that large monetary outlays are a necessary condition for exercising constitutionally protected free speech rights. They rely on the bizarre logic that, because our primary media happen to be controlled by corporations who use dollars as a unit of access, we as political actors must follow suit. This simply is not the case. The Greek agora and the Roman forum were political venues precisely because any citizen within them had equal power to engage in persuasive discussion with any other citizen present. All citizens had free access to the venue.

Radio, by contrast, has a finite number of usable frequencies, and television has a finite number of channels with substantial viewership. These media forms are far scarcer – and therefore far more expensive for the author – than, say print media was at the time of the American Revolution. Moreover, the relatively small market in these media means that increased demand during presidential elections rapidly increases the price of ad space. The structure of telecommunications limits the number of political ads that can be aired, so that large ad buys partially offset their added content by crowding out other, less wealthy advertisers.

Both radio and television also allow only for one-way communication, from the advertiser to the content subscriber. Broadcast advertisements therefore treat the viewer or listener as a mere receptacle for persuasion, and not herself as a persuasive, human voice. In conversation, the immediate proximity of the speaker to her listener is essential to speech – one must both attempt to persuade and be open to persuasion to engage in political discourse. This mutual discourse helps prevent the propagation of false or sensationalist rhetoric by exposing speakers to constant evaluation and rebuttal. The Court does away with the multilateralism of politics when it concerns itself with “the size of the audience reached” and not with the size of mutually engaged citizenry. The Court removes a further check on absurdity when it legalizes anonymous contributions, whereby the “speaker” need never expose him-, her-, or itself to any public scrutiny whatever.

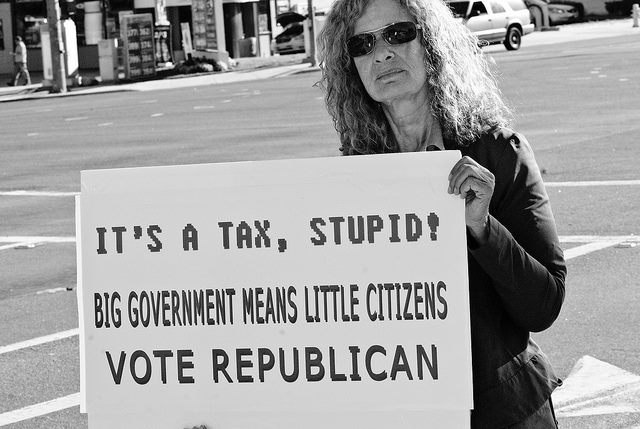

Finally, it does not take a pessimistic view of society to believe that hyperbole and misinformation can skew electoral outcomes. Regardless of how much a candidate’s policies benefit me – e.g., by guaranteeing affordable healthcare – I am unlikely to support him if I cannot trust his character – for example, because I believe that he is a radical Islamic militant bent on global domination. We check shallowness from the permanent opposition by holding out the promise that it may one day inherit the reins of government, with all the responsibility that entails. When it comes time to rule, the opposition must have a workable plan, or else it will fail as a government and be booted out of office in the next election.

When apolitical actors like corporations and unions (neither of which can hold government office) become politicized, this check ceases to function, as attacks on the ruling coalition need no longer be grounded in reliable alternatives to achieve the actors’ legislative goals. Baseless attacks, do, however, serve to ingratiate the candidate or party that they aid, allowing these sometimes-libelous organizations additional access to candidates, and perhaps winning candidates’ support for narrow policy goals, like lower corporate taxes or protectionist labor laws.

The First Amendment protects against a tyrannical government by guaranteeing the relatively equal ability of citizens to create and disseminate content critical of government practices and elected officials. It operates on the theory, expressed by Madison in The Federalist No. 10, that many, relatively equal factions will balance one another to prevent oligarchy. Equalizing economic conditions within politics promotes a meritocracy of ideas better than a system that equates economic success with political profundity. This meritocratic system ensures the ultimate stability of democratic states. At a moral level, it recognizes citizens’ individual worth. At a practical level, it provides an institutional outlet for citizen’s frustrations, thus alleviating the risk of violent revolution.

While a political sphere entirely separated from the economic sphere may, in fact, retain some inequality – e.g., in speakers’ background knowledge or rhetorical skills – these skills are at least relatively amenable to self-improvement and relevant to political processes. In contrast stands wealth accumulated by the selling of products or services, which entails no such persuasive prowess, but, indeed, quite the opposite: profits, the surplus wealth of business, arise from the brute force of desire compelling economic activity. In no event should the public welfare be conflated with this private satisfaction of desire, as public legislation deals necessarily with emergent societal needs that lack microeconomic analogues. Neither should matters of public welfare necessarily be subject to the wills of the economically successful, as the selflessness of authentic public service transcends the personal enrichment inherent in capitalistic enterprise.

—–

The essence of human action is the spontaneous creation of something entirely new – a tool, a product, or an idea. Food, drink, and the ingredients therein are consumed almost immediately following their creation. They lack any permanence whatsoever except as an eternally recurring component of the natural cycles of life. This type of consumption comprises a biological imperative, which a human can forestall only by causing his or her own death. The unending cycle of life enslaves all biological creatures, and in our need to satisfy it we are no different from any other living thing. The market economy and the division of labor mean that few of us actually produce the goods we consume for sustenance, yet subsistence labor remains: we still must work for money to trade for the basic needs of life, and labor for which the laborer gains only the means to provide for his or her own continued existence remains in principle the same component of the cycle of life, only that a sophisticated system of trade has been introduced to regulate this cycle.

If subsistence labor was all that humans could accomplish, we would be indistinguishable in function from the simplest living substance imaginable, because such labor is itself only the state of having life. Thus labor, taken by itself, is a purely natural and not at all moral, thoughtful, or self-reflective.

An entirely laboring species would interact entirely with nature in its raw form. We are far more used to engaging with the enduring products of work – the chair in which you are sitting, the buildings in which you live and work, the screen on which you are reading this post. All of these more permanent tools and edifices arise from a surplus of labor capacity beyond that needed to satisfy the basic needs of life. From this surplus work arise objects meant for use, rather than for consumption. That these products last beyond the life of their creator distinguishes them from mere consumable goods and creates the enduring, man-made world with which are most familiar.

Durable creations are thus also the chief defining feature of human activity and, indeed, of human excellence. The ability to transcend natural imperatives implies and affirms a hierarchy of action in which the most fully human (I pointedly do not say “best,” “most moral,” etc.) of behaviors is to divorce oneself entirely from subsistence labor and create only lasting products and ideas. The capitalist system – as do all economic systems – provides a framework for the production and distribution of durable goods, but durable ideas can arise only within a political, not an economic, forum.

Human excellence materializes through politics when an action is endowed permanence by memory, that is, when it is found worthy of remembrance. Only this intergenerational transmission can bestow upon intangible goods, like stories, theories, or deeds, the same permanence that exists in the creation of lasting material goods like chairs and computers.

Unlike material goods, however, ideas can last as long as the species. A wooden chair will eventually decay, but the ideas of Socrates can endure indefinitely in the minds of each successive generation. Even were the chair built of solid titanium, guaranteed to last for all of civilization, still the idea, taken for granted by us, that this oddly shaped metal construction is meant to be sat upon must endure if the chair is to endure. If the idea is not passed on, then even this presumably permanent structure becomes only so much raw material. Intangible goods – stories, theories, and ideas – thus contain the ultimate seeds of permanence and therefore of true human excellence. That such intangibles require a public forum to thrive underscores the fundamental importance to humanity of a healthy political realm.

The central role granted to money and monetary expenditures threatens human excellence in the political realm because commoditization can exist only where goods are treated as substitutable. Both the strong formulation that “money is speech” and weaker formulation that “monetary expenditures are necessary for political speech” imply the commoditization of the forum, and therefore the substitutability of the speech therein. I highly doubt, for instance, that HGTV cares whether they are airing a Romney ad, an Obama ad, an anti-smoking ad, a pro-gay marriage ad, or an ad demanding more prisons, so long as they receive the same amount of money for each one. The “pay to play” mentality, inherent in markets, hinders the introduction of new material to the discourse and limits speakers based on apolitical, economic characteristics.

Because the market limits space in the forum, individuals who have not been economically successful are also denied the ability to become politically successfully. They are doubly robbed of the capacity for human excellence because failure within the market structures that allow for the shadow excellence of producing durable goods implies exclusion from the political forum in which alone can one achieve the greater excellence of producing durable thoughts.

The commoditization of the political forum surrenders the political realm to a handful of wealthy individuals, creating a de facto plutocracy within an otherwise democratic forum. Against this stands the general American assumption that casting a ballot is the ultimate form of democratic expression, and so exclusion from speaking publicly in no way entails the surrender of governmental power. A ballot, however, can in no way be speech in that it is both anonymous, therefore not human excellence, and a prescribed choice, therefore not creative or spontaneous. The dialectic that shapes politics and policy is constituted by the creation of ideas that frame our modes of understanding the world. Surrendering that dialectic to market forces is not identical with surrendering partisan control of the White House, but it is identical with surrendering control of the expectations and priorities by which policy is judged.

We interact far more with man-made objects than with the raw, natural world, and so we are conditioned to understand and interact with the man-made world. As any millennial trying to teach a grandparent how to use computers will attest, we also become conditioned to the particular objects that dominate our world growing up. We are similarly conditioned to think in a manner consistent with the dominant modes of thought to which we are exposed. When we are exposed to the thoughts and thought processes of only a few perspectives, we are conditioned to think in relation to those standards. Thus, an oligopoly of political speech entails an oligopoly of thought.

Speech is not a good for purchased, but an activity in which to engage. A narrow perspective, an enforced dialectic, an economically dominated public forum, and corporate control of access to political notoriety undermine political liberty, human excellence, and our collective future.